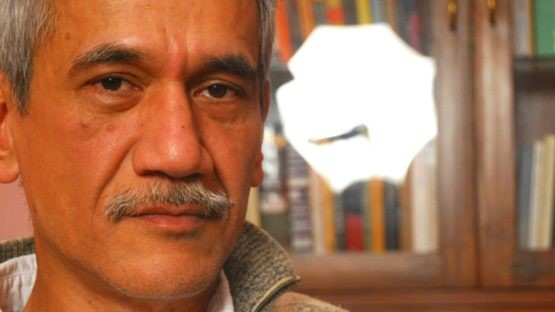

Sunil Gupta was born in Delhi, India and has spent time living in Canada, London, and New York. His photographs have appeared in numerous solo and group exhibitions and are in the permanent collections of museums in the United States, England, and Australia. He writes frequently about gay culture and history.

SP:A brief introduction to your early education?

SG: I went to St Columba’s and migrated to Montreal just before graduating and did a final year at Montreal High. Subsequently, I did two years of junior college at Dawson College in liberal arts followed by an undergraduate degree in Accountancy at Concordia. Then I went to New York to do an MBA in Finance and dropped out to study Photography at the New School for Social Research. My teacher there, Lisette Model, persuaded me to take up photography. Then I went to England to study Photography full time, ending up after five years with an MA from the Royal College of Art (1983).

SP: What is your background?

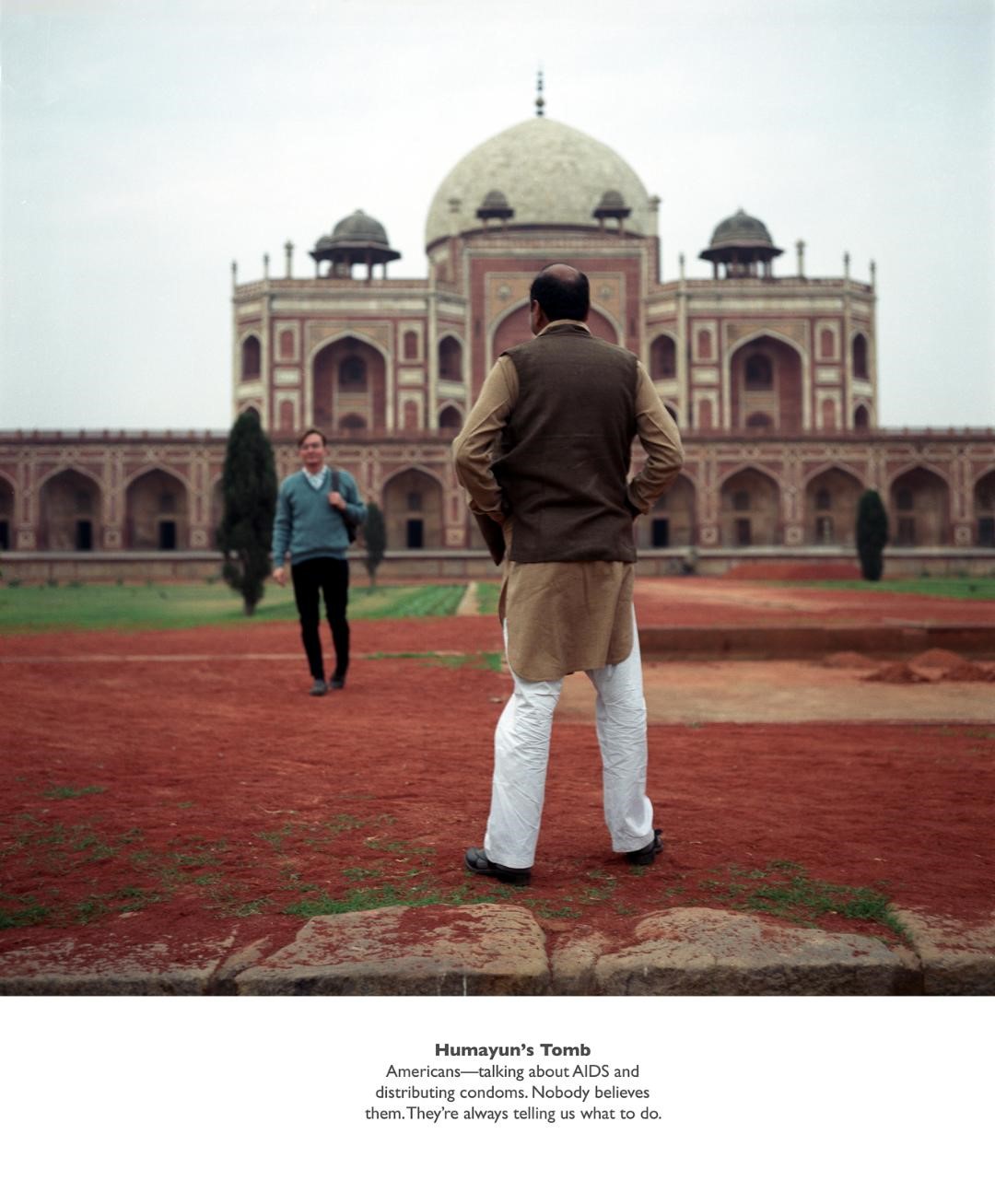

SG: My dad was ex-army and from a UP feudal background, although he had traveled to England before WW2 for training and returned eating beef and drinking Scotch. Mother had been left behind as a child by Tibetan migrant workers in Darjeeling, adopted by a British missionary who sent her away to boarding school to Amritsar and then to college (Kinnaid, Lahore). They met in Delhi on a blind date in the 1940s when he returned from the war and she was working in South Block and living an independent life. They lived in Delhi after that mostly in East Nizamuddin and she became a teacher at DPS (Mathura Road) when it was still in tents. I had an idyllic life till we left for Canada commuting between Nizamuddin and Gol Dak Khana (school) with Humayun’s Tomb as my playground.

SP: What advice would you give to an amateur photographer wanting to change their passion into a full-time profession?

SG: I would say, go for it. There’s nothing like an opportunity to say what you feel with pictures. It’s not the most paying job, nor the most stable. I’ve had to live on social security and handouts in between things. But, it’s saved my life as I’ve been able to be me throughout my life and not have to worry about what some boss might think back at the office or my family back home.

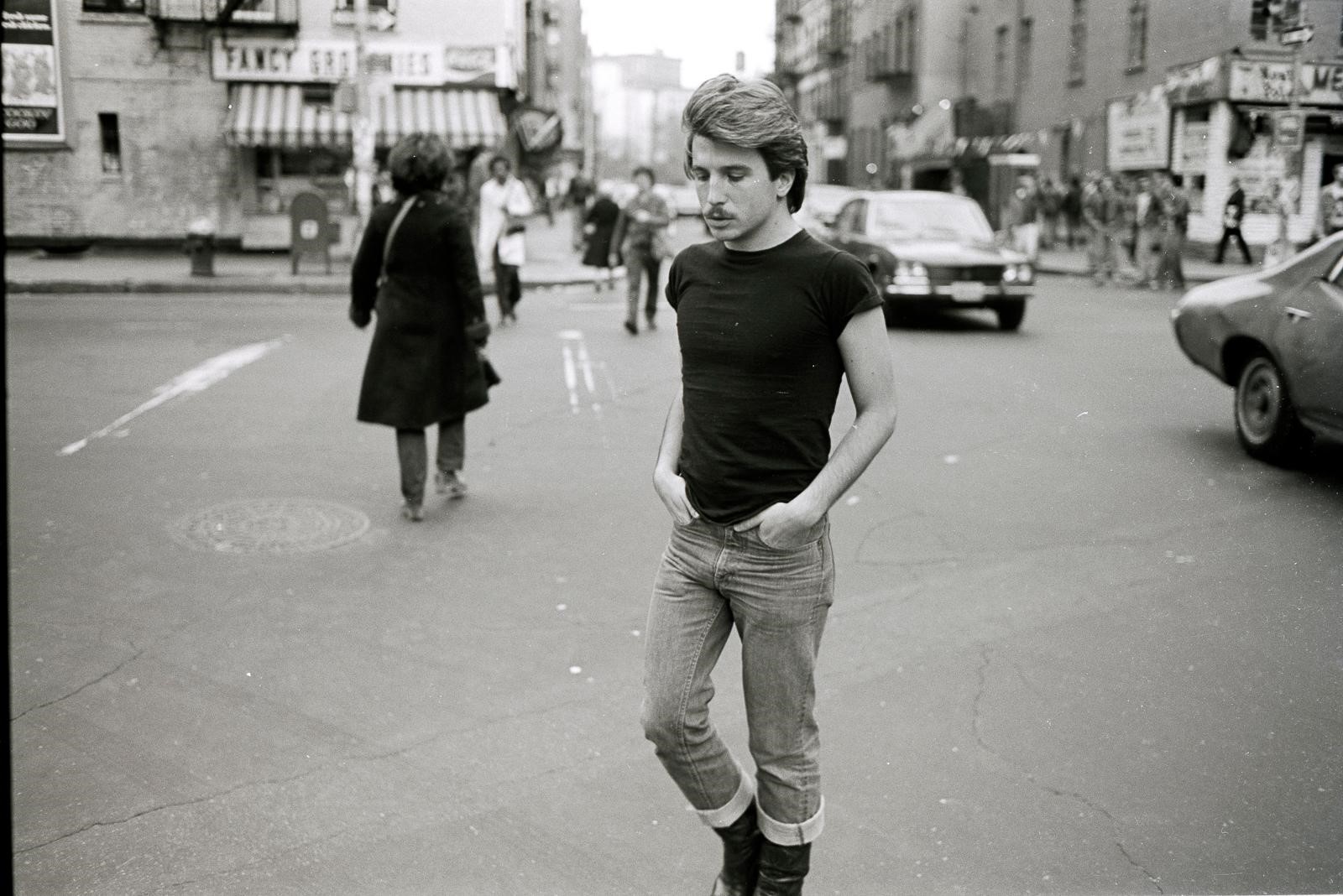

SP: You recently collaborated with Thomas Cawson, creative director at Helmut Lang, to revisit your Christopher Street, 1976 series for their collection. How was the experience of revisiting your work in 2020 for the artistic-fashion collaboration?

SG: It was extraordinary. I had never done anything like this before. I’m a little wary of such ideas as it’s usually not possible to repeat an idea in a different time and context. Here we were talking about a forty-four-year gap, although we were in the same location, and much of its facades are preserved, the time of year was all wrong. Furthermore, I had shot the originals over several weekends on my own in a leisurely fashion. Now I was expected to shoot everything, around twenty-two outfits, all in one day. As well as do the edit from some three and a half thousand exposures and make print-ready files by the end of the same evening. I was very anxious about it on the way over to New York, having to coordinate with the team, pray for no rain, hoping the camera and the tech would work. I learned a lot about fashion; everything happens at the last minute, the weather is always wrong, you can’t repeat a set up because the models have gone to other shoots, and there are a lot of people involved, more than forty on the day. I could see neither the clothes nor the models till the last minute, so there was barely any time to appreciate the visuals I was dealing with. My biggest anxiety was that the people would be terrible, it’s a prejudice I have from the media – but in fact, Thomas and his team were wonderful calm people to work with. It was amazing finally to have an ‘opening’ of the new and the old photographs at the Helmut Lang store in Manhattan. Would I do it again? I am not sure…

SP: If you could choose any of your previous projects to revisit today, which one would you choose and why?

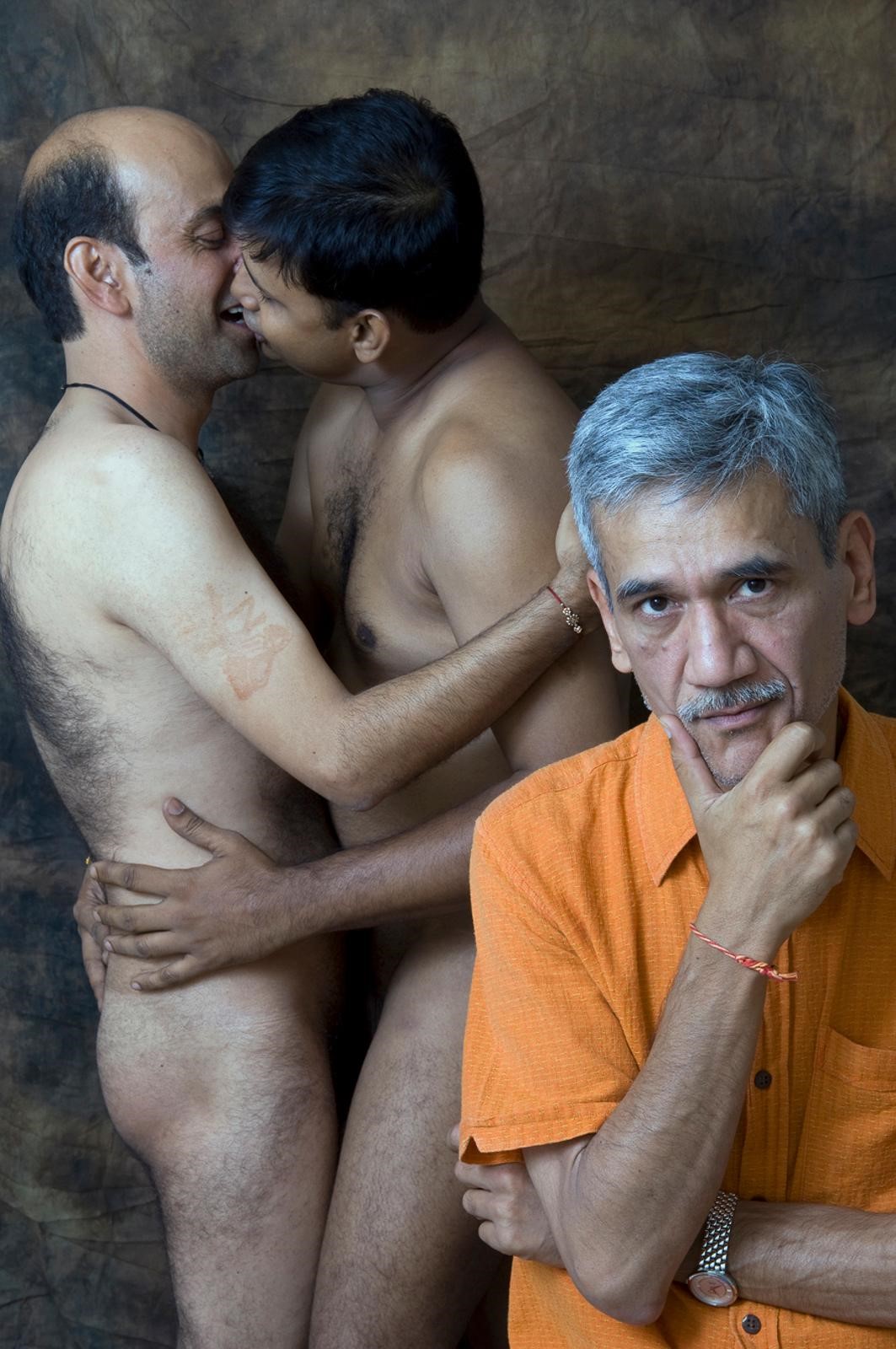

SG: I think, “Exiles”. Most of my life and work has been taken up with the question, “what does it mean to be a gay Indian man?” In that project, I barely touched upon it as I had so little time and such few resources to travel back and forth from London to research and shoot it.

SP: What makes a good photograph?

SG: It’s in the eye of the beholder. We bring our cultural history and baggage to each image and it either appeals to us or moves us in some way. Every picture I make has a life of its own; how it’s received and which ones get to be collectible and which ones end up at the bottom of my hard drive, never to be seen again. It’s all very subjective with no rules. I’m against the idea that there are great photographers and great photographs.

SP: What drew you towards photography as an artistic medium?.

SG:I grew up in Delhi at a time before the internet and TV, so all we had were movies and picture magazines. I loved the movies, even the big Bollywood tearjerkers, but it seemed a media beyond my reach. We barely had a telephone. But father did have a camera and I had a buddy at school who was equally interested and we both had willing sisters who could model and it went from there…. Of course, arriving in New York in the mid-1970s and seeing a brave new world of over fifty commercial photography galleries and the history of photography on display in the museums cemented my interest.

SP: You practice consists of not only photography but also video installation works as well as curation. What has your experience been as an artist and a curator within the diaspora and queer artistic community?.

SG:I have been very fortunate, in that I emerged after my MA into a London that was in the midst of not only an aesthetic revolution, post-modernism but also a political one, post-colonialism. Along with some of my peers of color, I turned my back to the commercial art world of Cork Street with its dealers and high prices and headed south to cross the Thames to the town hall to learn about visual art and cultural policy, engaging with communities and working towards social justice for all marginalized groups. I was able to enjoy theory and practice in a capital city, unlike my American peers, who tend to be a bit stuck in ivory towers as their real politics are so removed. I spent my time going to meetings — policy meetings, queer meetings, AIDS meetings, photography meetings, and writing papers. By the 1990s this coalesced into Arts Council of England support for separate institutions Autograph for Photography and INIVA for visual art. Both are still going, which is amazing. I got involved with starting them up and had a funded curating franchise to start a production company, OVA: The Organisation for Visual Arts, that came up with and placed art shows in museums and galleries in the UK. Queer art never really found a formal voice till “Queer Theory” came along in the later 1990s. Between 2000 and 2003 I was fortunate again to work via an academic grant for three years to explore AIDS in India. The work from that was included in the show that Radhika Singh curated at the Visual Arts Gallery, Habitat in 1994. It led me to move back to Delhi in 1995 which seemed short of things related to photography and/or queer so that’s where I put my energies. It helped to discover Nigah and become part of it, and to get the support of the Vadehra Art Gallery to promote photography.

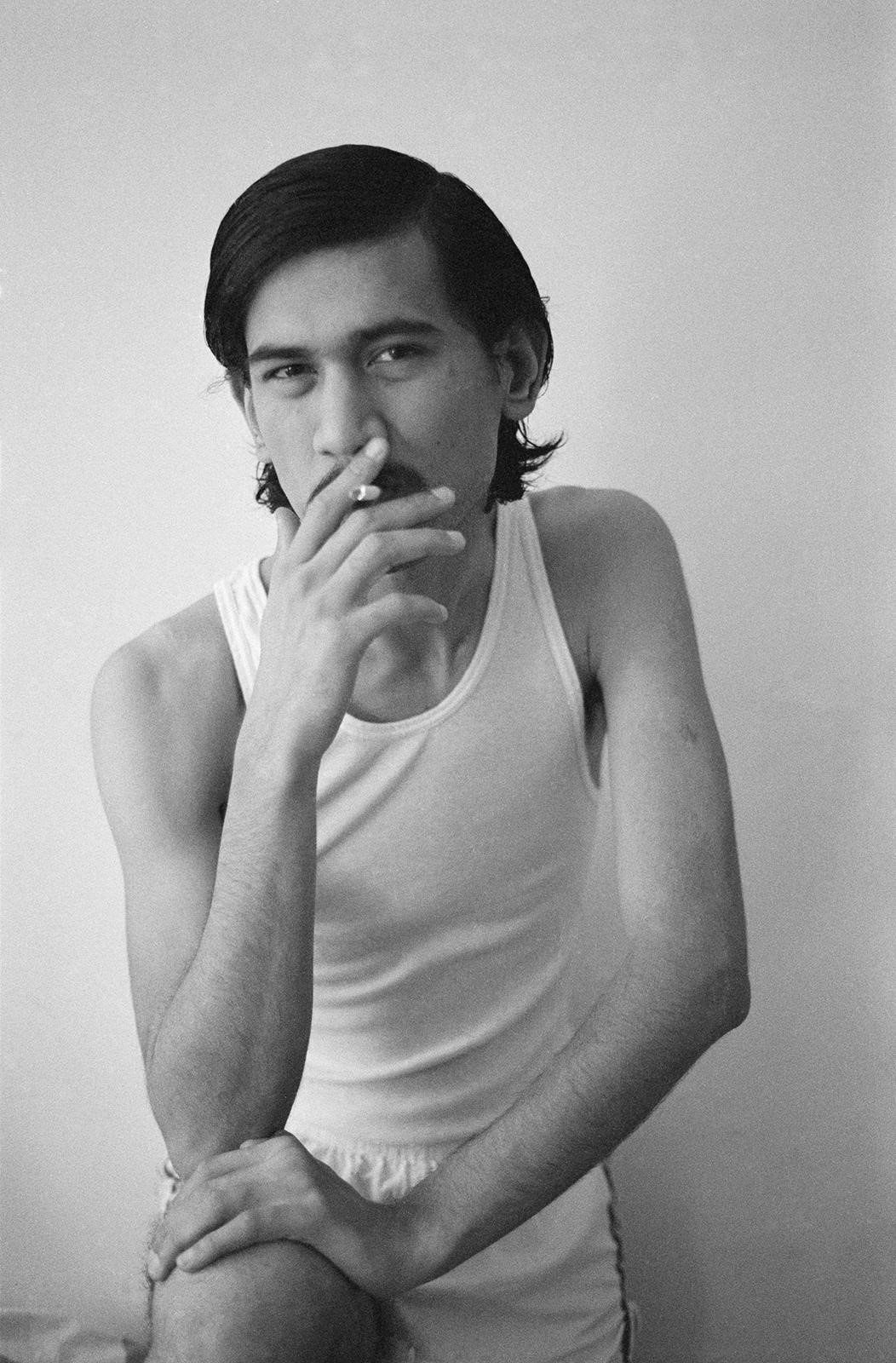

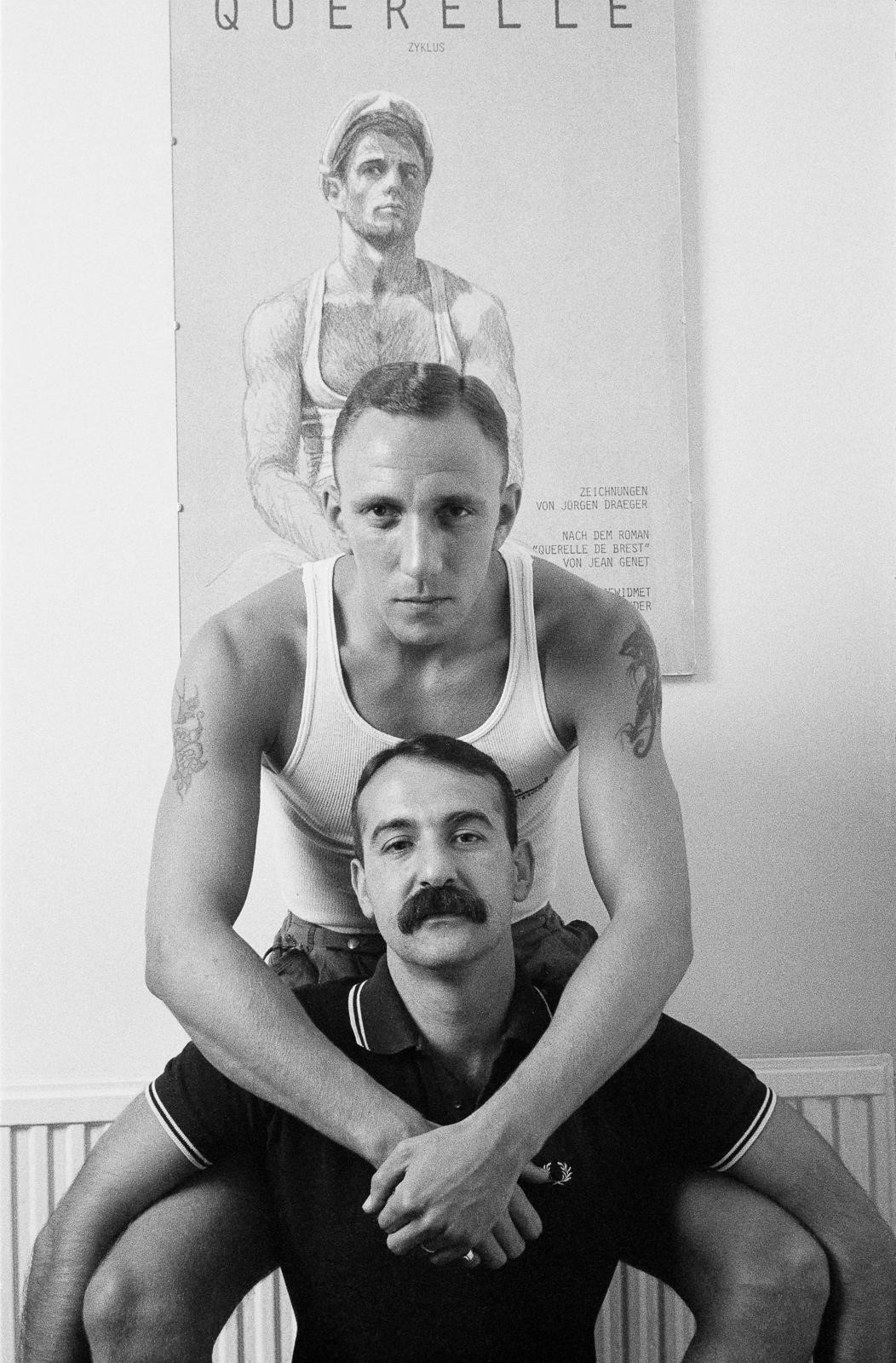

SP: Your photographic works have often envisioned the city and its public spaces alongside images of the queer community. Would you like to comment on this synchronicity or tension in your photographic oeuvre?.

SG:I’m a product of the early gay liberation movement, when to be out and visible was essential to procure social change. So I look for it everywhere I go. Of course, there has been nothing like Christopher Street in the 1970s since then in my experience. Even the original street has been gentrified and the gay men have moved off. I am a product of big cities, and I am aware that you have to fight for your place in them. People used to tell me not to mention that I was gay or HIV+ in Delhi drawing rooms and I thought, heck no, where is my space in this city?

SP: What are you working on at the moment? How has the ongoing pandemic and its effects on everyday life affected your practice?.

SG:This year I have a Residency from Studio Voltaire in London to work with the Imperial Health Trust in two London hospitals; St Mary’s, Paddington with HIV survivors, and Charing Cross with people undergoing gender reassignment surgery. But of course, the Covid-19 pandemic has meant that this is not when they want an artist lurking in the hospitals. And, I am not sure I want to be in hospitals right now either, so unfortunately it’s on hold. Last month I had an opportunity to make a short video called “Dream” in response to four-set questions from a curator for broadcast on an Instagram TV channel they were running. However, the same Studio Voltaire is now running a program called “Desperate Living” for LGBTQ+ people during the pandemic in which they have invited artists to make a body of work in a collaboration with the community. I am making a moving image digital piece with an HIV peer group in East London called Positive East. The turn around is quick and I hope to get this out by the end of June.

Image Courtesy: the artist and Hales Gallery, Stephen Bulger Gallery, and Vadehra Art Gallery. © Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2020

Find out more about the artist:

https://www.sunilgupta.net/about.html

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/sunil-gupta-4953

https://www.sunilgupta.net/christopher-street.html

https://www.halesgallery.com/exhibitions/136/installation_shots/