Vibha Galhotra is a New Delhi-based conceptual artist, working in a variety of media, including sculpture, photography, printmaking, video, drawing, and text. Her work is influenced by nature, climate change, and the anthropogenic issues of our age. Her large-scale sculptural works address the shifting topography of the world under the impact of globalization. She has shown extensively in India, New York as well as internationally, with many projects that involve diverse communities and their regions. Galhotra currently is a fellow of the Jerusalem International Fellow Program, 2020. She was awarded the Asia Arts Future Award, 2019, the Asian Cultural Council Fellow, 2017, and the prestigious Rockefeller Grant, 2016. Galhotra was born in the North of India, where she spent her formative years doing her Bachelors in Fine Art at Government College of Arts, Chandigarh followed by Masters of Fine Arts at Kala Bhavana, Visva Bharati University, Santiniketan, India.

SP: Your art practice is not confined to any medium or material. How do you perceive the inter-media practice of yours and how do you decide your mediums?

VG: The choice of material is often spontaneous. Mediums are the tools to express my ideas or story. Every work demands its own flow and own material/s. So the challenge is not in shifting from one discipline to another, but what I can do to fully express what I want. The core concept is more important than the material. And the best-case scenario is where they compliment each other. My process first begins with story/concepts. I think of many things, usually, the ideas I pick from are my readings, research and the environment around. Then I look for the best form to tell the story. The material/medium occurs to me in the process. I need to be physically involved in the process to transform my energy into it. Unless I’m working with my hands, to have that sense of molding materials into something, I don’t feel comfortable.

SP: What is the politics of the materials that you use?

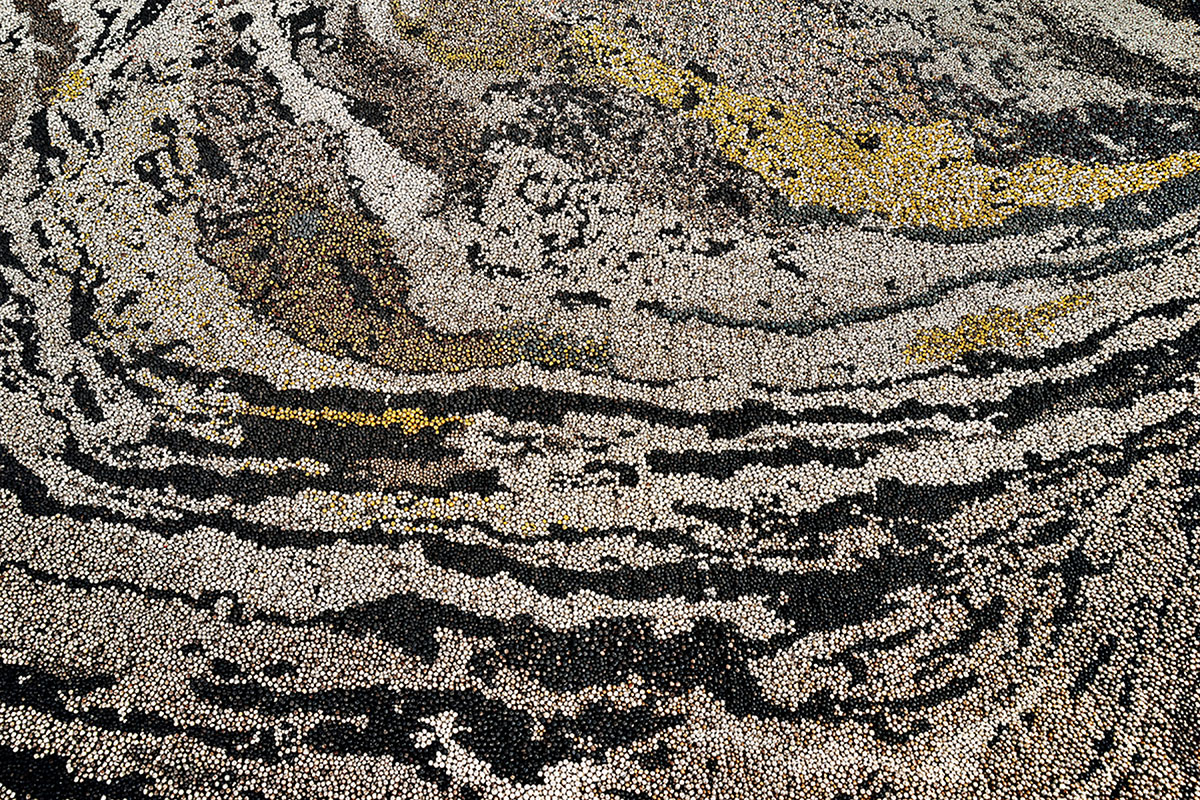

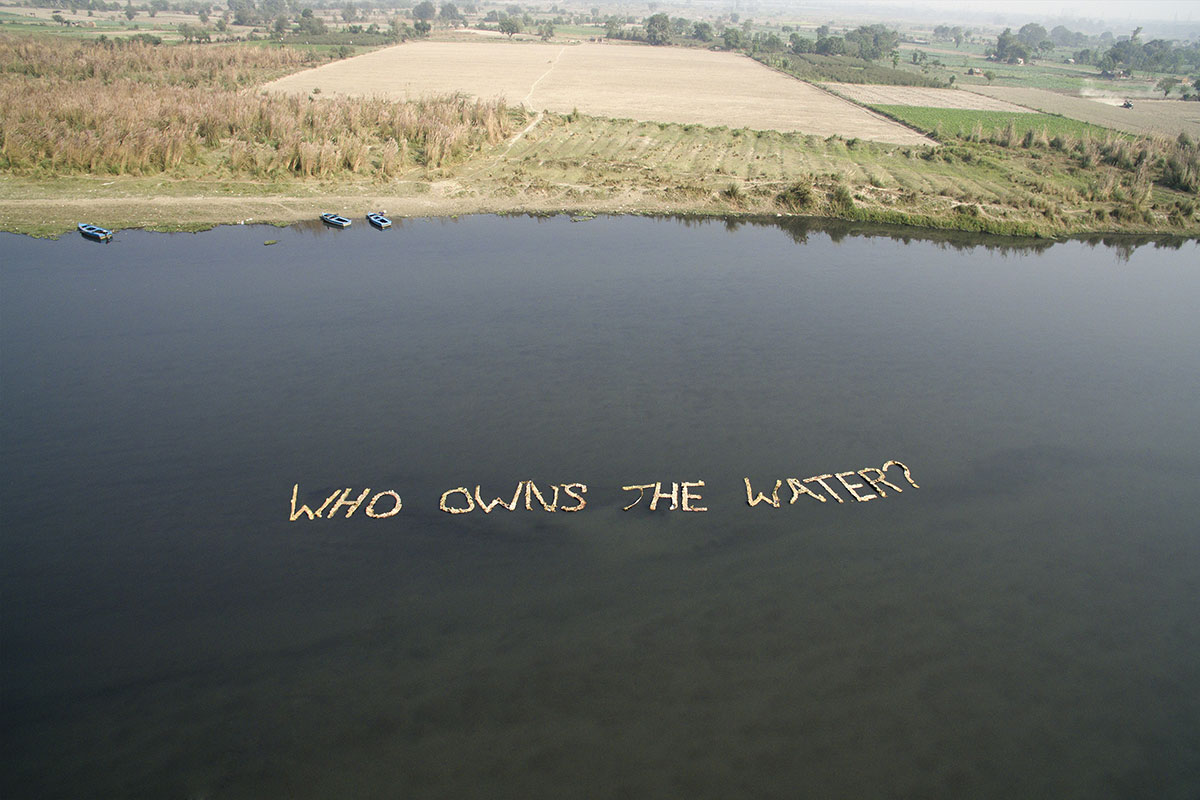

VG: I use local and found material, so definitely they carry the local context with all the reason for its existence. For instance, in the site-specific work, I did in Mongolia titled Who Owns the Earth? examining human impact on the earth and the shameless claim of its ownership. Being called the Land of the Eternal Blue Sky, Mongolia and its indigenous and nomadic traditions of being with nature are particularly vulnerable to climate change. I used horse dung as my material, available in the landscape to write the words of my concerns and let it be there in the land to the parish.

SP: You often use found objects in your work. What are these found objects to you?

VG: I always had a habit of collecting things/objects that resonated with me. They overtime formed an archive of sorts resurfacing in my works in different ways. The interesting thing about these objects is that they always carried the residues of the past with them.

For example, I did installations with found tree branches in concrete, metal bird nests, and whatnot. It is always fascinating for me the kind of unique stories these found objects tell. Another work I would like to mention is The Restlessness Rose Garden based on the work of a Spanish poet Alfonsina Storni, the work title also was borrowed from one of her writing works, the work was having these magical moments of living through her memories and converting them into these visual references and mixing it with my memories of collecting those objects.

SP: Tell us about your research on intervention on the subject Anthropocene. When did it occur to you?

VG: From the very beginning, I was always inclined towards nature and was more drawn towards finding its wonders and hidden mysteries. I was high on its beauty, especially during my college days in Santiniketan. My shift from Chandigarh to Santiniketan to Delhi transformed my understanding of the environment and the questions we pose to it.

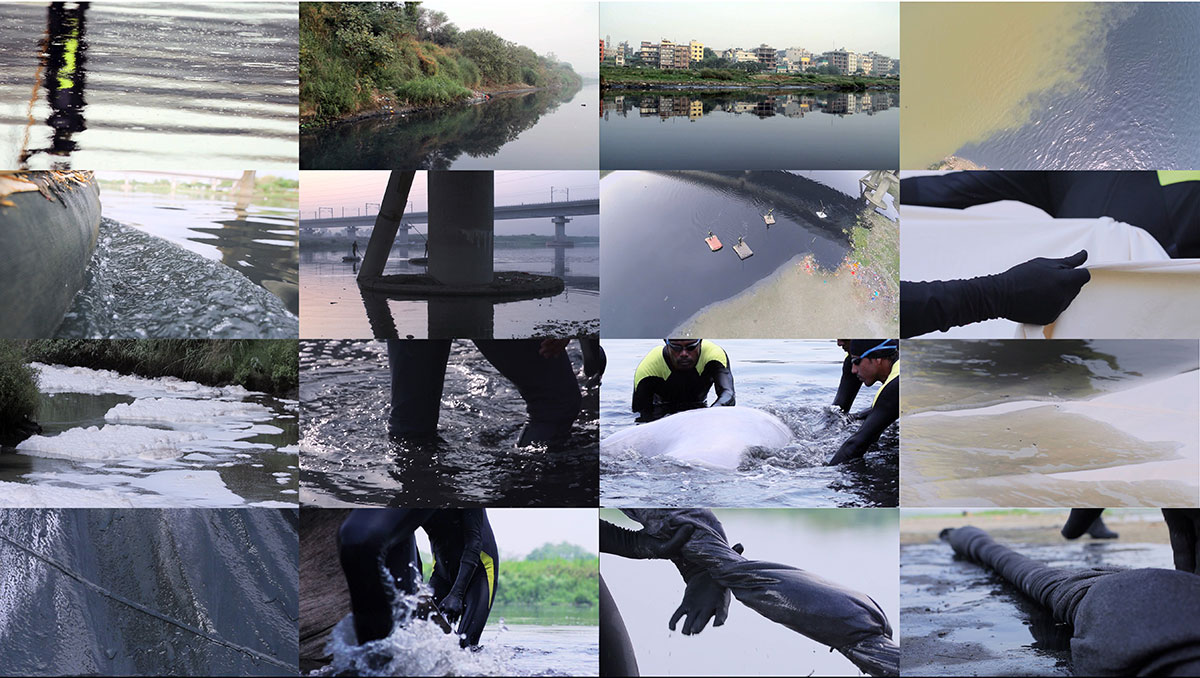

Being a migrant in Delhi, I always had this organic bent to address urban issues. Early on, I was invited as an artist for the Greenathon project to clean the river Yamuna by NDTV in collaboration with KHOJ International Artists’ Association. During this process, I encountered the river Yamuna (one of the major rivers crossing Delhi) that I mistook for a sewer for a long time after migrating to Delhi. On this first real encounter with the river, I was speechless. I couldn’t stop thinking about its condition and toxicity embodied within its flow. I started documenting the river without an intention to create a work out of it.

The idea of creating work and dialogue began after an incident with a couple doing their ancestor puja (prayer) and going for a holy bath at the river ghat. They were offended by me calling the river dirty and stopping them from taking bath in it for the concern they might catch some disease, but they rather challenged my presence around the river. That moment of brief conversation with them left me in this theatre of absurd and this contradiction of belief and reality, faith and science. The experience moved me to make a range of works around the condition of the river with all its socio- political, economical and ecological structures including a short film titled Manthan in 2015. The film invokes a legend from Hindu mythology in which the gods churn the ocean to obtain the nectar of immortality. Through a performative gesture, it examines the prospects of ecological threat and envisions a process of churning the deleterious out of the Yamuna.

Simultaneous with my engagement with the river Yamuna, I was researching the debilitating natural resources across the world especially due to human intervention. I learned about the word ‘Anthropocene’ which was coined in the early 1980s and became known in the 2000s after was used by Paul Crutzen, an atmospheric scientist to constitute a new geological epoch. The term has been a contested one for almost two decades and is still in extensive usage.

I was also particularly interested in how the human impact on nature is damaging developing countries like ours in contrast to the developed nations.As an artist, I wanted to contribute to this urgent conversation in some way. Even though a visible change is hard to bring we can at least try to bring awareness to the pressing environmental issues of our times.

SP: What is your take on the climate change and Culture divide due to the same?

VG: Climate change is real, very real. It is the result of the damage done by the forces of late capitalism, which also has brought in a huge scale of class and cultural divide. From the very beginning, capitalism has made evident that it intends to compartmentalize the world into forms of individual ownership governed and regulated by nation-states and global corporations. The idea of collective co-existence, economically, culturally, and environmentally is a very rare phenomenon today. In this way of operating even the ideas of sustainability are often profit-making enterprises.

SP: What is your position as an artist in contemporary times?

VG: I am an observer of my times and yes I happen to be an artist.I feel, as an artist living in turbulent times such as ours, it is important to contribute in small and big ways to the well being of our environment. As much as we desire radical changes it is also crucial to generate awareness about the socio-political issues that bear upon us today.

SP: How do you perceive activism in art? Are the two discourses Art and Activism different?

VG: Art and activism are different methods of engaging with real-world issues. However, there are many instances in history where both of them aligned and worked together. While activism is about contesting the status quo for active change, art bears the potential to simultaneously imagine a new world. In my opinion, the methods of art and activism have to work together and learn from each other. Having said that, I do not see myself as an activist, for me what is important is to express the concerns I have about the world through my artistic practice.

SP: Tell us about your process of thinking and executing an idea.

VG: I will say that I’m in a continuous process, usually beginning with reading, and researching, which eventually translates into the stories that I decide to tell through my work. Sometimes I succeed in this process and sometimes I don’t. What I enjoy is being part of this duration where an idea becomes an artwork and takes a life of its own. For me, I am successful as an artist when my work can move people emotionally and translate into slow changes in perception about the world we collectively inhabit today.

SP: What are you working on at present?

VG: Post pandemic unlock, I have been busy working on my new film, which hopefully will be showcased in my solo this year end or next year. Also I finished and sent in my work for the 2nd part of the Asia Society triennial in New York. I am also a Participant of the Jerusalem International Fellow Program, 2020. It got postponed to late 2021, so I will be there soon but have already begun interacting, identifying and working virtually with my collaborators.

Image Courtesy: Vibha Galhotra

Find more about the Artist and the Artworks:

http://www.vibhagalhotra.site/

https://naturemorte.com/artists/vibhagalhotra/

https://sculpturemagazine.art/a-conversation-with-vibha-galhotra/