Shalini Passi: India and its culture are an inherent part of your work, can you tell us about what first drew you to the country and what you find so inspiring about it?

Waswo x Waswo: I came of age in America during the social upheaval and transformation of the 1960s. Many of the youth in those days were looking eastward for alternatives, and I myself fell under the spell of Jiddu Krishnamurti and also the beat poets who were glamorizing India as a grittily spiritual, non-materialistic society. But it was my father’s stories and photos of India that really captivated me. He had been based in India during World War II, and kept a wonderful photo album I often used to page through in my youth. The cover was labeled, “China-Burma-India” in hand-written gold ink, and the tiny photos inside told his tale as a Captain in the US Army as he encountered the streets of Bombay, and later, Karachi and the foothills of the Himalayas. Some of the photographs were obviously bought from vendors, showing landmarks in Colaba that we still see today, while others were personal, such as an image of my shirtless father standing outside his army barracks with a barefoot kurta-wearing Indian boy at his side. Beneath that photo was written “Captain George Waswo with his Houseboy”. I look back to it now and realize how odd it was that he wanted a photograph with his houseboy, both smiling like equals before the camera. The houseboy stands very proud, with arms crossed, and gazes directly into the camera. I don’t think most Indians of the era would have been photographed with their house staff in such a manner, nor would the British. It is a very American photograph.

For some reason India, as a geography and a people, became lodged within my head. Though I didn’t have a chance to visit until 1993, it was always a mysterious something that I would dream about again and again. After living in India for almost twenty years, India has become home for me. I no longer see it as mysterious in any way, or, to use that dreaded word, “exotic”. India has all of the pros and cons that most countries do in our postmodern age, but still there is something magical about it. It’s hard to put a finger on: morning calls to prayer and evening bhajans, drinking chai from small clay cups, the way strangers will greet you in the streets of small towns and villages with wide innocent smiles, spotting a mongoose on the way to the studio…

Shalini Passi: In your work, you collaborate with a variety of local artists in Udaipur (where you are now based why is it important to you to keep alive these traditions of hand-tinted photographs?

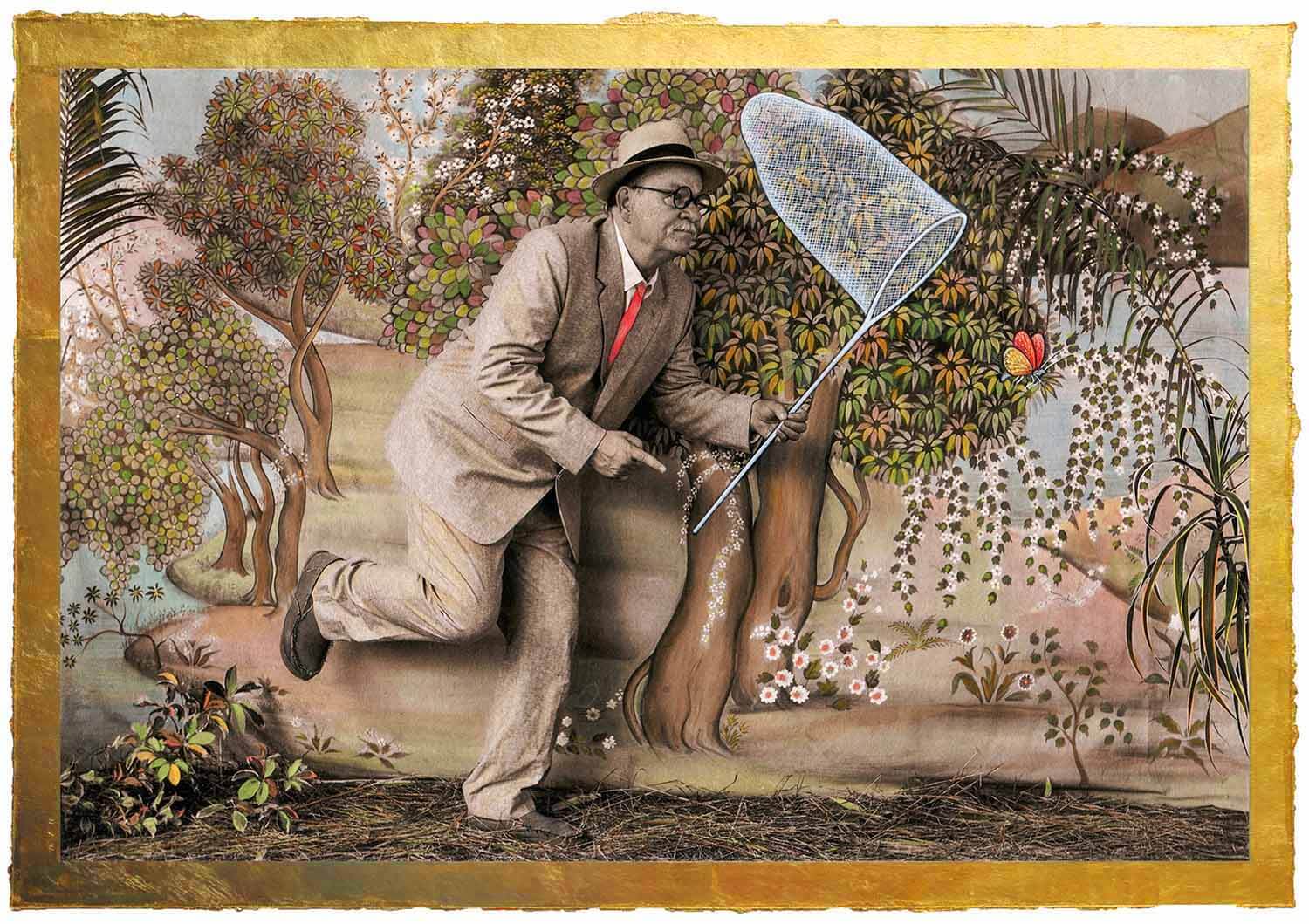

Waswo x Waswo: My studio basically makes two bodies of work. There are the miniature paintings that I do with the team of R. Vijay and Shankar Kumawat and Dalpat Singh, and there are the hand-tinted photographs that Rajesh Soni hand-colours. The two series actually are parallel and interrelate to one another though they are seldom exhibited together. The little fedora-wearing man in the miniature paintings is most often seen besides his Rolleiflex camera, and the hand-coloured photographs can be imagined as the photos that he is clicking during his bumbling adventures in India. The miniaturists that I work with were all engaged creating low-quality tourist souvenirs before I met them. Even though they had good traditional training they were stuck in these mindlessly repetitive jobs. Rajesh Soni, too, was not utilizing the skill of hand-colouring that had been transferred down to him from his grandfather. It was very sad. The tourist market has cheapened many of these old traditions, which is one reason that our images often poke fun, in a subtle way, at the tourist and the tourism industry. There is no way to really view our hand-coloured photographs but in real life; it is the only way the subtly and the softness can really be seen. Losing skills such as Rajesh maintains would be a tragedy. Meanwhile, Indian miniaturists find it difficult to find students within the current economics of our time. No one wants to take the many years they need to perfect their line and master the brush.

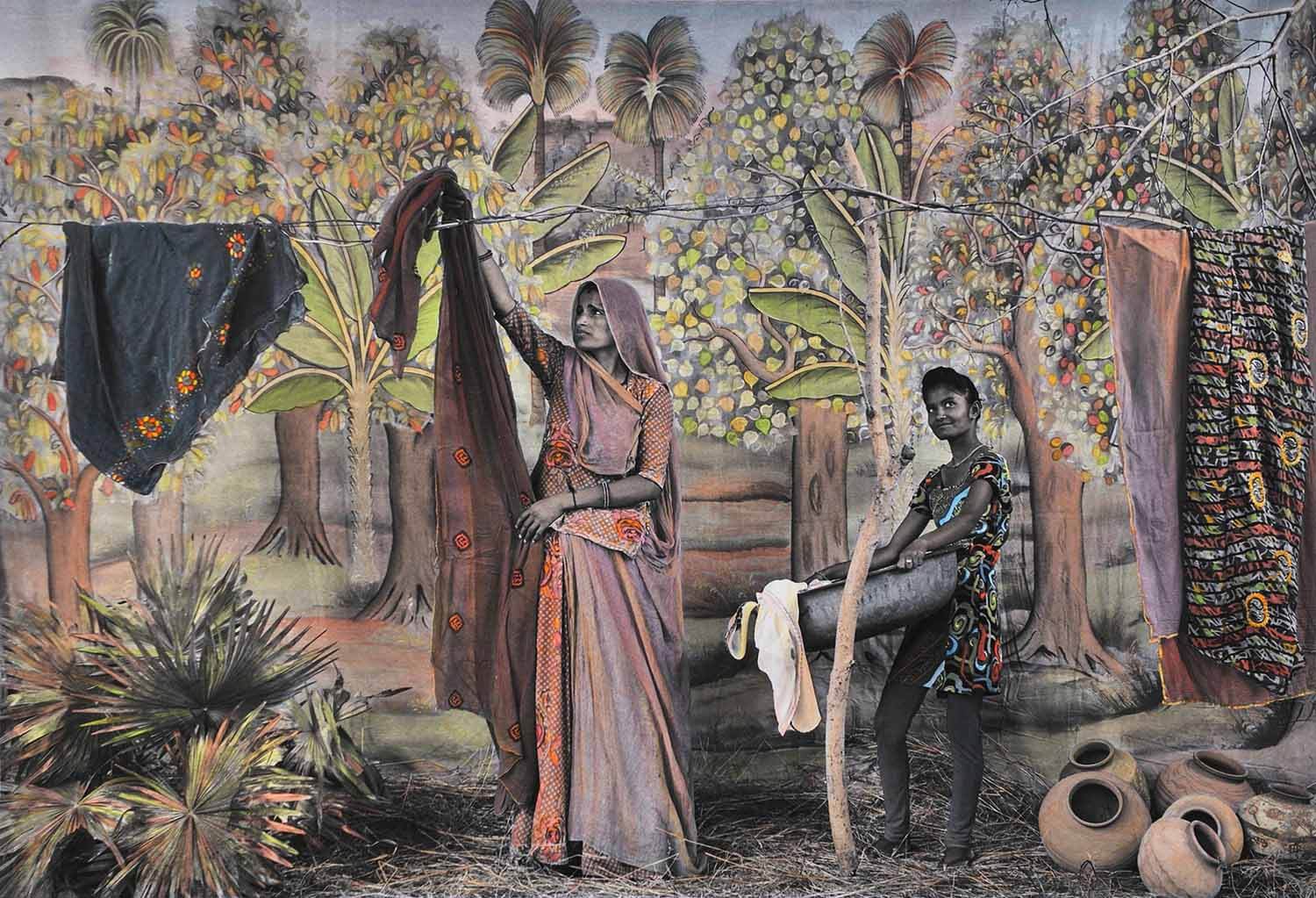

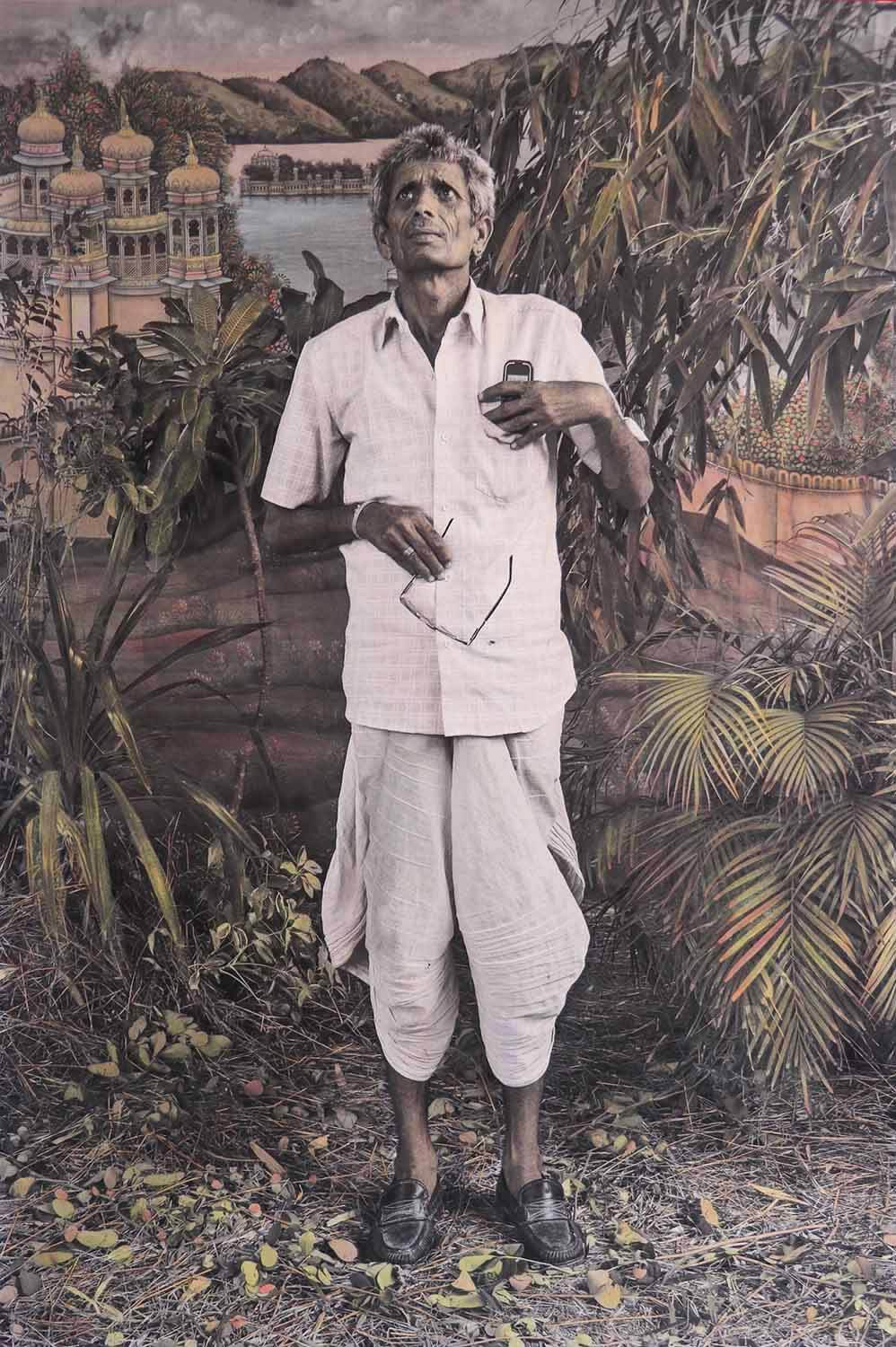

Shalini Passi: You have said before that you do not agree with the description of your works as ‘nostalgic’ because they depict contemporary scenes from rural Udaipur; can you tell us a little bit about this choice to use an old fashioned medium for capturing modern-day India?

Waswo x Waswo: It always depends what a person means when they say “modern-day India”. There is the modernity of the urban centers, and the ever-expanding technologies and infrastructures that is the promise of the new India. But village and small-town India is still very much alive and a part of the current reality. In Rajasthan the fields are often plowed by oxen with wooden plows, village women make and repair garments by hand, swords and knives are sharpened by travelling workers going from village to village on their bicycles. When I photograph such people I’m not looking backward with dreamy eyes, but I’m acknowledging their presence within the context of the modern day. The use of the hand-coloured black and white digital print reflects this dichotomy. Our photographs straddle a line between an old technique and a new, and viewers often remark that they look both vintage and contemporary at the same time, and that is exactly the reaction that I hope they will have.

Shalini Passi: You have previously worked with more experimental media such as installation, video, and even a comic book; what did these media enable you to do that is not usually possible with the medium of photography? Do you intend to explore working with any of these media further in the future?

Waswo x Waswo: I know I get pegged a lot as “that American that does miniature paintings” or “that guy that makes hand-coloured photographs”, but I see myself as an artist that utilizes many forms. In the past we’ve exhibited textual works, video pieces, terracotta sculpture, and now, marble. I think those works often get skipped over by our fans who are eager to talk about the miniatures or the photographs, but for me it is all a part of a larger expression. If my team and I are a rock band, I am a songwriter, so the concepts always derive from me. Like any good artist ought to do, I explore that which is known to me. I never claim to be documenting anything. Instead, I’m creating a sort of continuous visual diary of my experience as a foreign interloper in India. What media I will use in the future depends upon what stories I may want to tell. I don’t see myself as chained to the current mediums that we use. Perhaps, like George Harrison of the Beatles famously did, I’ll decide to add a sitar and tabla to the rock band and shake the whole thing up. My art evolves slowly, but it has to evolve. For an artist to remain stagnant is to spiritually die.