Ankon Mitra is the Design Director & Co-founder of Hexagramm Design, New Delhi that specializes in designing hotels, resorts, landscapes of different scales and high end boutique residential developments. Akon’s explorations are usually renditions of origami as architecture, which he terms as Orchitechture. He has been enthusiastic about origami and consequently developed algorithms leading to a plethora of forms and techniques for sculptural paper installations with the interplay of hues adds to the effect of light and shade. He accepts exploration of a craft needs with considerable dedication and perseverance that often results in extremely fascinating results.

SP: When did you first come about this idea of fusing Origami and Architecture?

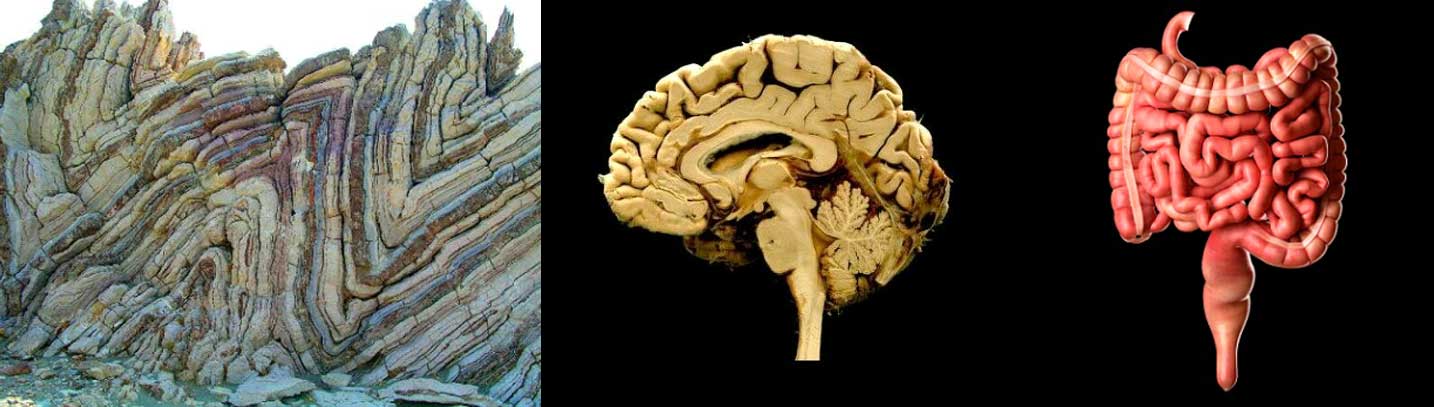

AM: I came to a comprehension of folding in 2008 through a gardener in the Kew Gardens in South-West London. He pointed out the folds in the leaves of a Sycamore Maple (I clicked photos, image below) that got me thinking about why nature uses folds in all that she creates. This is a massive thesis in itself (not suitable for this short Q&A, but it would suffice to say this) – from the world of insects to gargantuan geological processes, from the human body to cosmic level events – all are governed by the logic of folds, or by forces and processes – which are made visible through folding.

If such magnificent arcs of creation are governed by folding, could human-created architecture remain unaffected by it? Folding is all around us in the simplest of architectural forms. If one looks at a room (the regular cuboidal kinds we all inhabit), the walls meet each other at 90 degree folds (usually), as do the ceiling and the floor with the walls. Without this ‘folding’ of the planes, even this basic architectural/spatial expression is not possible. Sometimes the simplest thing is not apparent unless we ask a specific question of it. Thinking back to 2009, as I started getting deeper into folding as a fundamental tool deployed by nature, I was able to stumble onto a new way of looking at Origami. That childhood craft of boats, paper planes, tippy-tippy-taps and flapping birds was no more that childhood craft. It was an immense interconnected universe of geometry, forces, logic, structure, sculpture and movement. In this rediscovered realm of Origami – I found that Biology and Robotics were talking to each other, Medical Science and Mathematics were in deep conversation, and Engineering and Art were shaking hands. If ever there has been a fountain of knowledge right under our very noses, which we have ignored it as mere child’s play, I would wager it is Origami. Thus in a moment of lucid epiphany, I coined the term Oritecture = Ori (Folds from the word Origami) + Tecture (from the word Architecture). The root word Oru means a single fold in Japanese, Ori means many folds. Kami/Gami as you would have guessed means paper. The word ‘tecture’ comes from the Greek root word ‘Tekton’, meaning designing, planning, crafting and building. Oritecture would therefore mean creating or crafting through folds, in other words Folded Architecture or folded creations.

SP: With this one of a kind fusion, introduce our readers to the philosophy and practicality that makes this idea so successful?

AM: Nature uses folding –

(a) To achieve deploy ability, create flexible systems which are adaptable to changes

(b) To save energy and optimize use of available resources

(c) To convert weak materials to strong using 3D geometric principles, thereby making them viable for use

(d) To do more with less – one solution serves more than one objective, preferably multiple objectives

Let me give a few examples. A type of Mushroom – Parasola Plicatilis, creates a gossamer thin canopy which is self supporting because of the presence of pleat-like ridges on the surface of the canopy; The common ladybug has wings hidden under its red shell and can deploy them by unfolding a Z-shaped mechanism in-built in the wings. When walking or not in need for flight, it protects the gossamer thin wings by packing them into one-third their regular size (as we pack our umbrellas when not in use). The Himalayas were formed billions of years ago when the Indian and Eurasian geological plates collided with each other and the sea bed buckled and folded up to form the mountain chain that we call ‘young-fold’ mountains. We can see similar ‘chevron’ folds in the rocks at various geological sites around the world. Our brain tissue and intestines are all folded up to pack maximum length into a minimum space, also to increase surface area for different purposes in the limited space of our cranial and stomach cavities. These scientific explanations sound dull to the non-initiate, but to those who grasp what this implies, we are talking about fundamental principles of how things work. Close your eyes and think for a moment. Now reopen them. How were you able to do this action? Because your eyelids have folds in them!

I came to the realization that the design/art fraternity is doing very little with this simple yet amazing technique gifted to us by nature. Efforts across the globe are disconnected and unconcerted. I decided that I must make my own small beginning – by applying this knowledge to things I understood a little bit – in the realms of art, architecture and design. Over the last decade my practice has implemented Origami in furniture design, outdoor and indoor sculptures, lighting installations, product design, toys, tableware, fashion, interior design, architecture and engineering. We have prototyped a foldable and portable Baby Crib for working mothers at factory and construction sites, designed a more efficient folded Hepa-Filter for an Indian Air-Purifier start-up company, worked with a cluster of shadow puppetry rural artisans in Andhra Pradesh to reinvent and revive their material – goat-hide / parchment leather into high-end export worthy lighting solutions, designed stage and backdrops for theatrical performances and fashion shows, mentored textile and fashion design students to create Origami haute-couture, launched a range of Origami tableware in India for the first time, and also inaugurated India’s first Origami Pavilion in a garden setting earlier this year. There are numerous realms yet to be bridged and folding will continue to cross and ford those frontiers.

SP: We would love to know about one of your favorite projects so far.

AM: I fell in love with a column at the Chennakeshava Temple in Somnathpura, Karnataka many years ago. Constructed around the 12th century AD under the reign of the Hoysalas, an anonymous sculptor had carved the stone in such a way as to give the impression that he had lovingly folded the hard granite. I sat in front of the column for an hour in stunned silence. Then I decided to create a folded column of my own to pay homage to that unsung hero who had folded stone with the might of his intellect and craftsmanship all those centuries ago. Thus was born ‘the Divine Axis’, shown first at the India Art Fair in 2018 by Art Centrix Space. We immensely enjoyed the process of creating this homage, going back and forth between sketches, drafted drawings, computer generated models, hand-folded paper models, 3D printed studies and finally the folding of aluminum and wood veneer of the final artefact. The original temple column would have been five thousand kilograms or more. Our free-wheeling interpretation was hollow from inside, and weighed a mere fifty! Thus the contemporary embraced the ancient, in an act of reverence, humility and reinvention.

SP: How has your education helped you become the person you are today?

AM: I feel labels create unnecessary limits for creative souls, but often when I get asked if I think I am more a self taught Artist or a trained Architect – I like to say that I am a ‘Researcher’. My earliest education happened in my formative years under the tutelage of my grandmother (Naani) and my Ma. They instilled in me an immense sense of curiosity of the world around me. This is my every curious ‘Researcher’ gene. This was followed by schooling at a Catholic institution which infused in me a rigour and discipline which I treasure to this day, because it affords to me a kind of fortitude and single-mindedness to create goalposts and then surpass them. The foundation of Architecture gives a three sixty degree perception of systems and processes that is critical in any kind of artistic or design project / intervention. From the technical to the socio-cultural, from the historical to the material, Architecture touches all aspects of making, and for that reason I am grateful to have come to art through the prism of architecture. I am especially grateful to my architecture education at S.P.A Delhi for providing me the skills and the knowledge to be an initiate in many disciplines, or in colloquial terms – a jack of all trades! Parametric Design allows for multiple bridges to form between the world of mathematics, computation, natural laws and the world of architecture and design. The stint at the Bartlett, University College London, gave me the insight to begin connecting the disparate dots, to see design and the world it responds to – as a continuum and not as isolated silos. I am seeped in the writings of Rabindranath Tagore, Patrick Geddes,Alan Watts. These intellectual heavyweights shine the light on the spiritual plane of our existence, telling us that we remain incomplete as physical, emotional and intellectual beings until we embrace and understand the true energies of the cosmos and its connections to us. In all the work that we do, we must embrace that sense of wholeness. And then we become complete, connected and one with all things. That is a life long journey of every artist, to find the pieces of jigsaw puzzle and then put them together to complete themselves. I would say I am incredibly fortunate to have found folding in my life.

SP: Tell us about Hexagramm Design, your architecture firm.

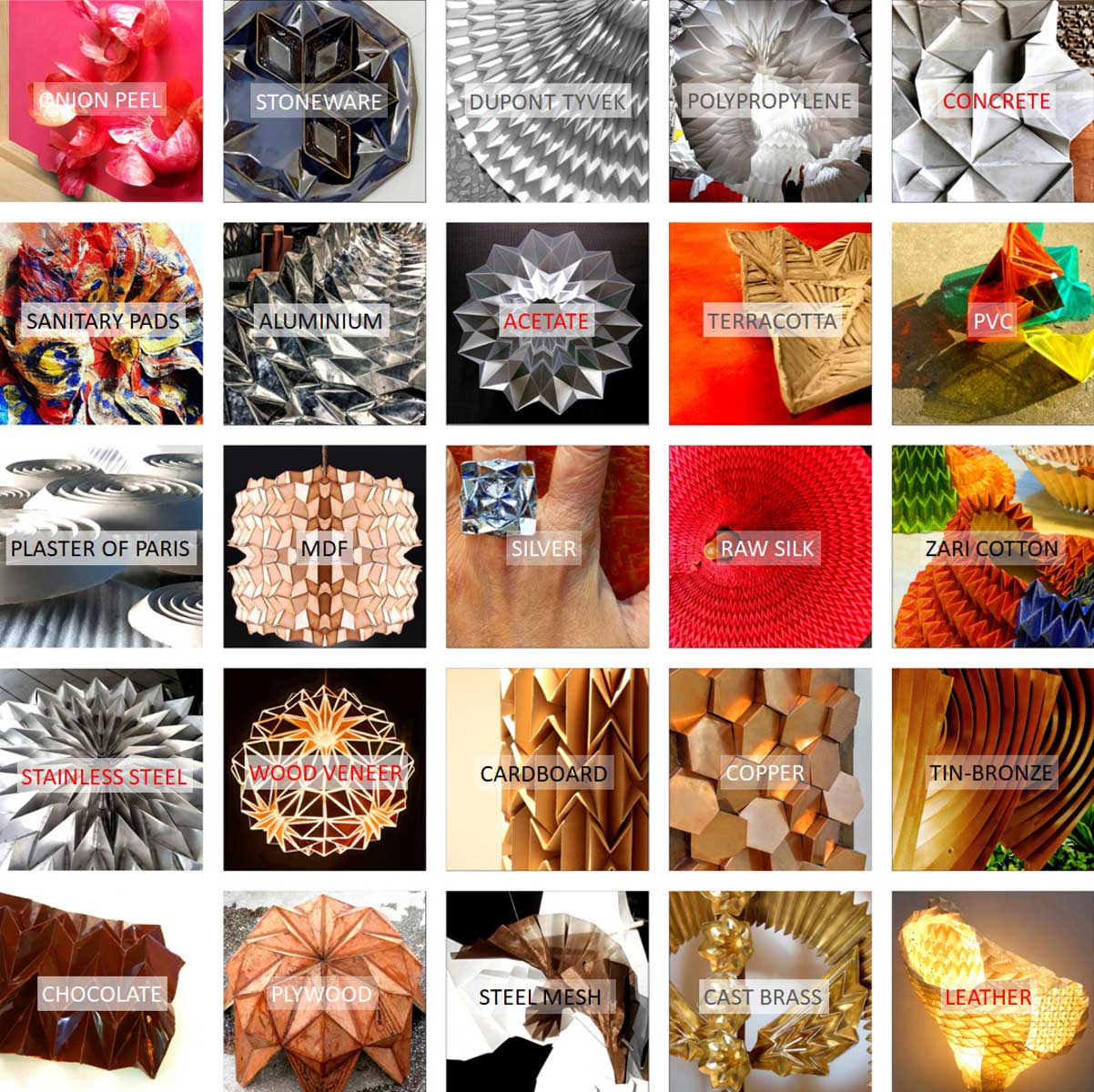

AM: Hexagramm Design was formed in 2007 on the back of a landscape design competition win. We are three partners in the Studio, architects and batch-mates from School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi. We have different specializations and Masters’ degrees – Urban Design, Sustainability, Parametric Architecture. This reflects in the diversity and scale of projects executed by the Studio since the last 13 years. We have designed city scale landscape projects, bridges and flyovers, hotels, offices, resorts, restaurants, retail as well as residential projects across different locations in India and of widely different scales. Our tiniest project has been a table top terrarium with an astonishing diversity of flora and our largest a 400 hectare smart city project. We collaborate with a lot of architecture and design practices, stay humble, love research and that has allowed us the opportunity to create a rich and very diverse portfolio of completed projects in a short period of time. The art vertical is now embedded within our architecture studio, which means architectural scale sculptures, outdoor installations and parametric architecture projects themselves embodying the spirit of art form a very niche and exciting realm in which our studio now operates. We also build and fabricate most of our projects ourselves which gives us a lot of room to experiment with new materials/techniques and use those material/process insights in a cross-disciplinary way. If I had operated as a conventional artist, I would have been limited to a few materials. But because I decided to erase the boundaries between my art and architecture practices (the art practice is fully integrated with the architecture studio) – the material palette keeps growing and becoming exciting not only for me but for the entire team. We are sought out for a lot of projects which are in the interstice of art and architecture. For instance we have completed a kinetic origami ceiling in one of our office projects. We designed, devised and fabricated the entire ceiling in-house. We are continuing to grow and evolve our workshop, which is an extension of the studio. Since 2018, I have been working on a personal goal of folding 150 different materials by 2022, which will be a nod to the 15 years of our practice. When I say 150 materials, all the different kinds of paper are counted as one material, so there is no cheating involved in this. Interesting (and unconventional) materials folded till now include Shola grass, Onion peel, wood veneer, chocolate, Dupont Tyvek, Stone paper (made from powdered stone) and Ficus leaves! We are at 74 materials currently, this quest will continue.

Image Courtesy: Ankon Mitra ; First Nature ; Kazuyo Saito / New Scientist; Mina Trikali / Natural History Museum of Crete ; Sciepro/Fine Art America ; Science Pictures Limited.

Find out more about the artist:

http://www.hexagramm.in/project-by-category.html

https://www.instagram.com/ankonmitra/?hl=en

https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/dvbx599xvz97lgtJIBoGQO/Sculptural-origami.html